Chiara De Dominicis, Alessandro Bratus (LMMP Italian Team)

Mapping Florence’s live music ecosystem offers valuable insight into the city’s cultural and spatial dynamics. The dataset, comprising 265 venues across five districts, highlights a significant concentration in District 1, particularly in the historic center, where 60% of the venues are located. This area’s prominence reflects its economic and cultural centrality. District 5, known for its extensive social spaces, accounts for 18% of all venues, while the remaining districts, primarily residential, host fewer venues. The dataset includes a diverse range of venue types including student and social spaces (22%), bars, restaurants, exhibition spaces, nightclubs and seasonal outdoor venues, each playing a distinct role in shaping Florence’s musical landscape. While small clubs, despite their limited capacity, contribute to the ecosystem’s diversity, large arenas dominate the city’s overall capacity.

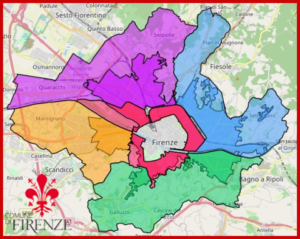

Figure 1. Map of Florence divided into its five districts. The uncolored central area represents the historic center, while the surrounding pink-shaded area corresponds to District 1, which also includes the historic center. The blue area represents District 2, the green area District 3, the orange area District 4 and the purple area District 5.

The concentration of venues in the historic center underscores the socio-cultural pull of these areas. However, the predominance of spaces primarily frequented by tourists, such as Red Garter and Fitzpatrick Irish Pub in the Santa Croce area, highlights a tension between urban transformation and what is perceived as “cultural authenticity” (MacCannell; 1973). While these venues do not explicitly define themselves as tourist-oriented, an observation of their clientele and event programming suggests that they cater more to external demand than to the needs of local residents. Similarly, spaces such as Ostello Bello in the Santa Maria Novella area and Yellow Square Hostel, located within District 1, further reflect this dynamic. Although these venues function as gathering spaces for international visitors, they do not inherently reflect the Florentine cultural context. Instead, their presence aligns with a service model tailored to a global clientele rather than addressing the needs of the local community. This trend is part of a broader urban transformation, marked by the rising cost of living and the increasing impact of tourism on housing and commercial dynamics. According to a recent study by the Centro di formazione e ricerca sui consumi, housing prices in Florence in 2025 are on average 16% higher than in 2019, making it the second most expensive city in Italy per square meter. This data highlights the connection between rising real estate prices and the concentration of venues in high-tourism areas, suggesting an ongoing redefinition of the social and economic function of the historic center. For instance, neighborhoods such as San Frediano, once working-class strongholds, have progressively transformed into tourist hotspots, leading to the displacement of residents and a reshaping of cultural practices.

On the other hand, Events like “Estate Fiorentina”, a city-funded festival, promote live music and cultural events across the city through a structured grant system. While this has supported institutionalized events in central areas, it has also progressively limited grassroots initiatives, including community-led concerts and informal cultural gatherings, particularly in peripheral areas, as a side effect. Nonetheless, informal and underground venues in outlying districts remain vital for sustaining Florence’s diverse music ecosystem beyond institutionalized frameworks.

The mapping dataset for Florence’s live music ecosystem focuses on publicly accessible spaces active since January 2023. Among them, six venues from neighboring municipalities are included for their cultural significance. These spaces, although outside Florence’s municipal boundaries, are integral to its music ecosystem, reflecting the city’s broader cultural, social, and economic interactions within its live music circuit. These include six venues: the Teatro Romano di Fiesole, a historic venue hosting diverse summer music events; two prominent techno clubs in Sesto Fiorentino and Campi Bisenzio; a former factory space in Campi Bisenzio known for its politically and socially engaged concerts and DJ sets; a long-established club in Antella (Bagno a Ripoli) popular among local audiences; and the Casa del Popolo in Grassina (Bagno a Ripoli), an important musical hub since the late 19th century. Their inclusion ensures a comprehensive representation of venues connected to Florence’s musical network. However, the analysis primarily emphasizes venues within Florence’s boundaries to maintain geographical consistency with LMMP guidelines.

Prominent in the dataset are “social/student” spaces, which in Florence often take the form of community-driven initiatives like ARCI-affiliated circles (Italian Recreational and Cultural Association) and cultural centers. While these spaces mirror trends observed in Milan, they also exhibit distinct local characteristics linked to the specific urban and socio-cultural fabric of each city. For example, while Milan’s urban structure, with its concentric rings, allows for a more dispersed distribution of performance spaces extending beyond the city center, Florence’s development along the Arno River results in a concentration of venues in the historic center and along the riverbanks. This urban layout influences not only the physical distribution but also mobility patterns for audiences attending live music events. Ephemeral spaces, such as certain busking sites and house concerts, were excluded from the dataset to focus on regular, verifiable events. Examples include house concerts organized by Associazione Culturale Senza Palco, founded in 2017, which emerged from the need to create spaces where live music takes center stage rather than serving as mere background entertainment in venues, fostering a more engaged listening experience. Additionally, various busking spots in Florence’s main squares or at Piazzale Michelangelo, regulated by the municipality. The dataset also acknowledges post-pandemic challenges by including historically significant venues that ceased operations due to COVID-19 but remain emblematic of Florence’s urban soundscape. Examples include La Cité, a literary café that regularly hosted live music events until the pandemic forced it to suspend such activities, and Auditorium Flog, the city’s only large venue, which remained closed after the closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This methodological choice aligns with LMMP’s aim to provide a robust comparative framework, while still recognizing the contribution of transient spaces to Florence’s musical landscape.

The comparison between Florence and the other cities mapped by the LMMP projects further highlights some specificities of the city as a complex urban musical ecosystem, shaped by distinct spatial and cultural dynamics. First of all, it is similar to Milan, the other Italian city in our aggregated data set. In both cities, the presence of social spaces that are occasionally used as live music venues is relevant – 19% of the total number of venues in Florence and 15% in Milan; art centres such as museums and galleries are another important part of the musical ecosystem in both cities, which only partially compensate for the lack of dedicated spaces for (especially popular) music performance. The Italian cities have the lowest proportion of dedicated music venues for non-seated music performances (live clubs) of the entire dataset (Florence: 3,44%; Milan: 1,65%), underlining the ongoing efforts to ensure the existence of such venues and their nurturing effect on the production of new, original acts.

Figure 2. Proportions of population/venue types in the LMMP dataset (Florence, Dublin, Birmingham)

In terms of overall capacity for participation in musical performance, Florence (with around 172,000 people attending live music events) is positioned between Birmingham (143,000) and Dublin (238,000), but in quantitative terms the broad profile of its music ecosystem is characterised by the presence of two main categories of venue, both adapted to musical performance. The first are churches (Santa Maria del Fiore, Certosa di Firenze), and the second are large outdoor and indoor performative adapted spaces such as arenas and stadiums (Mandela Forum, Fortezza da Basso, Stadio Artemio Franchi). The latter – including the Visarno Arena, a large open-air space for horse racing – are located in the more peripheral areas of the city and host major events with mainstream national and international acts that not only attract local audiences but also use the city’s touristic appeal to market major events. These include, as an example, a multi-day festival such as Firenze Rocks, which in 2025 will feature headline acts of the commercial scale of Guns N’ Roses, Korn, and Green Day. In Birmingham, the more relevant categories are large venues and urban outdoor spaces, and in Dublin the presence of small clubs and venues appears to be significantly higher. This is in line with the inverse relationship with social spaces in Italian cities (for 26% of them in Florence, music is their main business, while in Birmingham and Dublin this figure is 15% and 12% respectively). The incidence of venues that, despite hosting live music as their main business, still take the form of social spaces confirms the hypothesis that there is an infrastructural need for a reform of the music sector in the country to promote and protect smaller and dedicated music venues as part of a diverse and vibrant cultural ecosystem.